As millions of people across North America flock to swimming holes at nearby lakes and rivers to escape the heat, so too do billions of migratory birds.

But for the birds, these waterways represent far more than just an opportunity to cool off. They represent the best chance these birds have of surviving the combination of habitat loss and climate change that is putting so many birds around the world in peril.

Habitat loss is believed to be the number one driver of bird population declines around the world. And although climate change forecasts indicate the times becoming more troublesome in the future, many birds are already being affected by it.

So if you’re a bird that is not only losing large portions of your habitat, but also seeing the scant habitat that remains changing rapidly, what are you to do?

For billions of our continent’s migratory birds, the answer is to flock to the Boreal Forest.

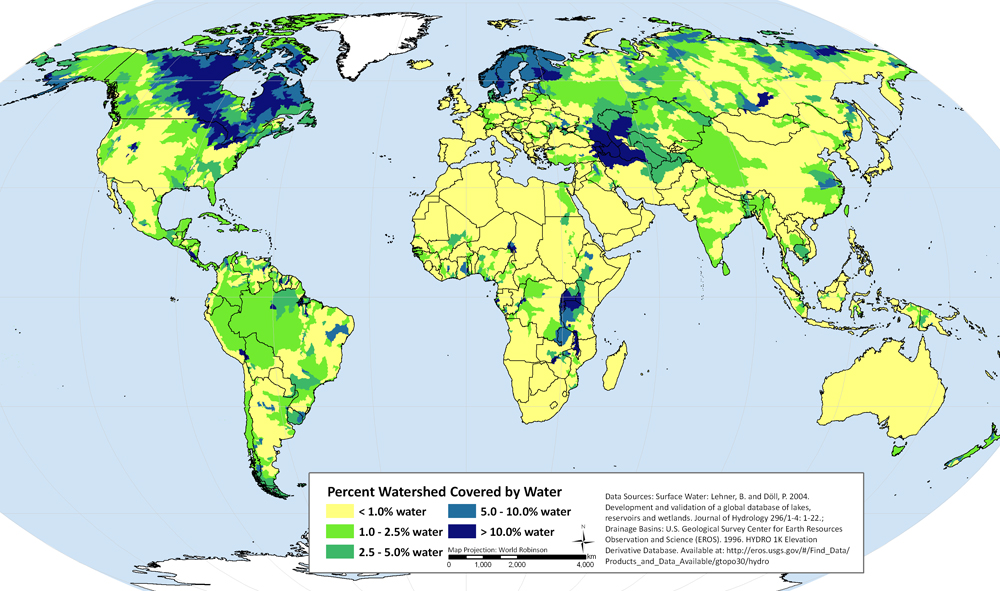

No place on Earth features more lakes and wetlands than the North American Boreal. Nearly half of the world’s lakes larger than 1 square kilometre (247 acres) can be found in Canada’s Boreal Forest, in fact. As can 25% of the world’s wetlands—critical breeding habitats for birds but also some of the world’s most important natural allies in curbing climate change. Wetlands capture and store exorbitant amounts of carbon; Canada’s peatlands alone, nearly all of which are in the Boreal, store the equivalent of nearly 750 years’ worth of Canada’s annual greenhouse gas emissions, for example.

This map shows just how much of the Boreal Forest (the majority of the dark blue area in Canada) is made up of lakes, rivers, and wetlands.

These immense expanses of water and wetlands have attracted birds for millennia. Shorebirds like the Short-billed Dowitcher and Solitary Sandpiper feast on the plethora of insects and small crustaceans on the shorelines of the Boreal’s many lakes. Waterfowl like the Green-winged Teal and Common Goldeneye thrive on the nutrient-rich aquatic delectables in those same waterbodies. The insects produced by the Boreal’s abundant waterways invite a host of insectivores, including some that snatch them right out of the sky (Olive-sided and Yellow-bellied Flycatcher) as well as those that prefer to pluck them off trees and the ground (27 types of wood warblers can be found in the Boreal during breeding season).

But as more forests are converted to farmland and as global temperatures continue to rise, the Boreal Forest increasingly offers a last glimmer of hope for some of North America’s birds being pushed to the brink. And the combination of its intactness and abundance of fresh water are the main reasons why.

Around one-quarter of the world’s remaining large, intact forest landscapes (think of vast expanses featuring not a single road or power line) can be found in North America’s Boreal. Around 80% of the forest still remains free of industrial disturbance.

This relative lack of a human footprint means that many of the Boreal’s lakes, rivers, and wetlands are still pristine and uncontaminated. Residents of these remote landscapes describe dipping their cups directly into rivers for a drink knowing that water hasn't been sullied further upstream.

It is this combination of size, habitat diversity, intactness, and abundance of pristine fresh water that keeps billions of birds coming back to the Boreal Forest each summer to nest. Nearly half of all bird species in the U.S. and Canada utilize the Boreal for breeding grounds, including 80% of all waterfowl species, 53% of wood warbler species, 93% of thrush species, and 63% of finch species.

While many boreal birds are surely in jeopardy—particularly songbirds and aerial insectivores that thrive in the southern portion of the Boreal where development has been most rampant (think Evening Grosbeak, Canada Warbler, Olive-sided Flycatcher, and others)—as a whole it remains one of the few habitat regions of North America where birds by and large are proving capable of holding their own.

Signs point to this incredible reliance continuing, if not increasing, in the future. A groundbreaking 2014 report by the Audubon Society found that many of North America’s birds are already moving north as a result of climate change. Many of the birds the currently breed in the northern U.S. and southern Canada are projected to expand their range further into the heart of the Boreal Forest in coming decades. In this sense, the Boreal will essentially act as a Noah’s Ark for birds and other wildlife that are unable to find suitable habitat further south.

So what can we do to ensure this continental bird nursery remains healthy and capable of supporting billions of birds for generations to come?

The simple answer: keep it intact.

As experience has shown us time and time again, the cumulative effects from fragmenting habitat into smaller chunks add up and as a result, ecosystems slowly begin decaying and are incapable of being self-sustaining over time.

Given how much of our continent has been logged, paved over, or turned into farms, the Boreal Forest offers us the last opportunity to find the right balance between conservation and development. We devote resources and put in place emergency plans when endangered species dwindle down to a handful of individuals. So why would we not treat the last few remaining large, healthy habitat expanses on Earth with the same level of urgency and care before it’s too late?

Within the scientific community, there is a growing consensus that we need to protect much more wilderness than we have historically, and ideally in larger, interconnected protected area networks. Most modern studies contend that around half of a large ecosystem or region must be off limits to development to maintain the full complement of species, communities, and ecological services. This is true for the boreal, as evidenced by the 1,500 scientists from around the world who penned a letter calling for at least half of Canada’s Boreal Forest to be protected.

How to get to that level of protection is either the challenge or the opportunity, depending on if you’re a glass-half-full or half-empty type of thinker.

First and foremost, Indigenous rights and sovereignty must be respected regardless of whether the discussion is about creating a new park or a new mine. There are hundreds of Indigenous Nations and communities throughout the Boreal, each with their own aspirations and desires for how to sustainably manage their traditional lands. Working in support of Indigenous Peoples and their efforts to protect their lands and waters will not only ensure wildlife is better preserved, it will also minimize the number of conflicts that arise over projects that are unwanted by communities but that receive government approval.

Second, priority must be given to areas that still feature large expanses absent of the human industrial footprint. Not only do these areas generally support the largest and most robust wildlife populations, but they also provide the geographical space necessary for niche habitats to move and adapt as climate change continues, along with the wildlife that depend on them.

Finally, areas not included in protected areas must still be maintained with leading-edge sustainability standards. Although much of the southern portion of the Boreal Forest has fallen victim to clear cuts, dams, and other harmful development, many companies are looking forward rather than behind and improving the ways in which they harvest resources from the Boreal. These improved approaches should be celebrated and continued to be improved upon.

There are countless examples across the Boreal that should give us hope. Indigenous governments are increasingly being recognized in Canada’s court system when it comes to creating new protected areas or fending off projects that lack the community’s buy-in or support—the Ross River Dena Council’s recent ban on mineral staking being one example. Many of these governments have or are in the process of developing land-use plans that map out what is to be protected, most of which see more than half of the region eventually protected—the Poplar River First Nation in Manitoba provides a good example of that, having protected 100% of their traditional territory (nearly 1 million hectares/2.5 million acres).

Two provincial governments, Ontario and Quebec, have actually committed to protecting at least half of their northern boreal regions. Succeeding in this will require a commitment to work with Indigenous governments and communities. The Moose Cree First Nation in Ontario, for example, wants to ban mining from the North French River—one of North America’s most impressive undammed and uncontaminated rivers. But achieving this requires buy-in from the provincial government—something they are still working to achieve.

As a signatory, Canada is committed to meeting Aichi Biodiversity Targets. Among these is a requirement of protecting at least 17% of the nation’s land by 2020. Although Canada’s current pace indicates it may not meet this by that year, the most logical place to start would be in the Boreal Forest.

It requires a shift in thinking, and one that sees the forest rather than just the trees. Given recent successes, the Boreal’s prospects are certainly looking up. The billions of birds that depend on the Boreal are sure hoping this momentum continues; after all, it may be their last hope.