This is a guest post that has been reprinted with permission by Emily McKinnon, Research Affiliate in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Manitoba. Check out her blog here: https://birdbiologist.wordpress.com/

Spring is on the horizon and birders everywhere are starting to get antsy for those first early migrants. This year is a very exciting one for me, as I’m waiting for the return of one of my newest study species – one of the most mysterious boreal songbirds out there. Right now, ‘my’ birds are out there with tiny data-logging backpacks on, fattening up deep in the jungles of South America, waiting to head north.

Let’s see if you can guess who they are. These small warblers are long-legged, but not always found on the ground; they are colourful, but camouflage well; they are loud songsters, but largely quiet on migration, and often missed at breeding sites; they breed in open bogs, mature aspen forest, or mature mixed woods, but most people live far away from their breeding range; they look very similar to two other warbler species, but they are genetically distinct so placed in their own genus. Here’s a recording I made of one this past spring if you need a big hint:

The answer is…Connecticut Warbler (Oporornis agilis)!

First let me just explain that this unfortunately-named species has little or nothing to do with Connecticut, at any point in its life cycle! The name came from a single specimen that was ‘collected’ (i.e. shot) over the state of Connecticut in 1812 by Alexander Wilson.

Check out that beautiful eye ring! Thanks to my field tech @KelseyDBell for taking the photo.

A better name for this species might be something more physically descriptive, like Blue-headed or Eye-ringed Warbler, or maybe something related to habitat, like Boreal Bog Warbler.

In general Connecticut Warblers have a reputation for being mysterious, shy, retiring, skulky, rare, or even ‘sluggish’! After my first field season with this species this past summer, I think this reputation is because most birders only ever see Connecticuts during migration, and they are fairly rare and quiet during this period. Connecticut Warblers also migrate later in spring than a lot of other species, so they easily miss peak spring birding in May. Fortunately for me, living in Manitoba, at the edge of the boreal forest, Connecticut Warblers can be found breeding within 45 minutes’ drive of my house! Delving into the scant literature on this species last winter, I realized that we might actually be losing the Connecticut Warbler before we even know anything about it.

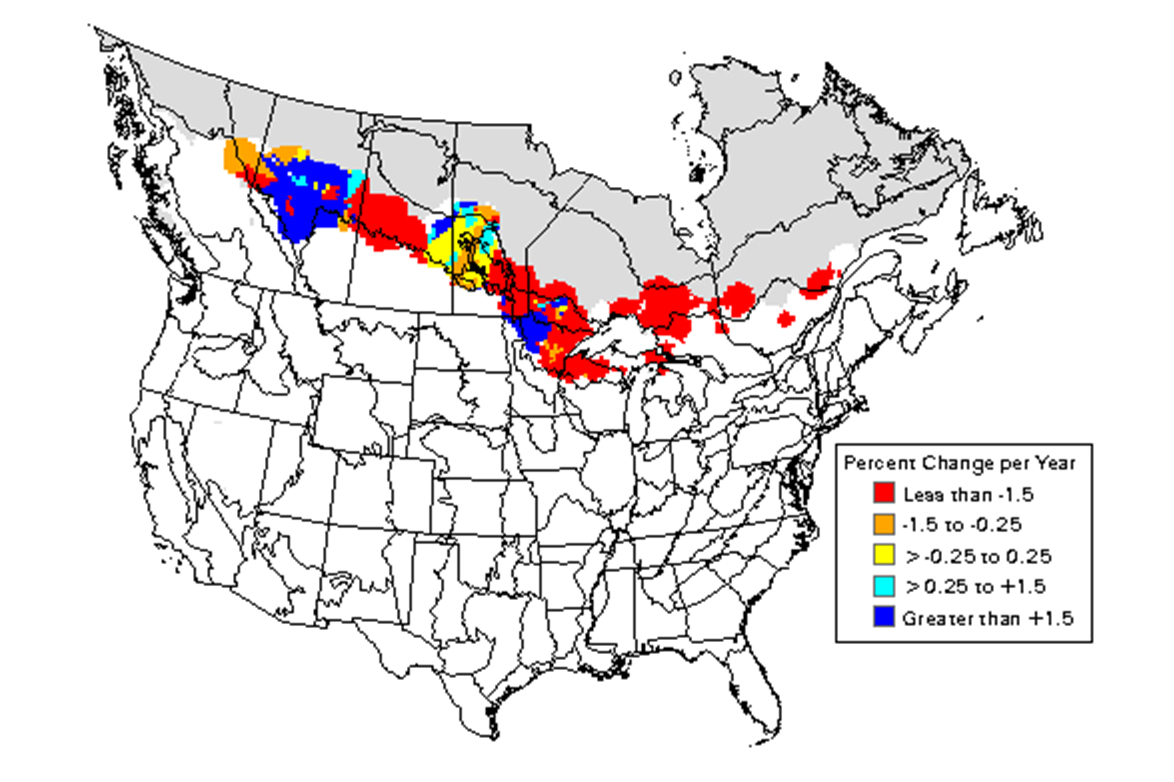

Long-distance migratory songbirds as a group are showing population declines across North America – my previous study species, the Wood Thrush, shows a fairly typical pattern of about 2% population loss per year over the last 40 years. The data for boreal songbirds are a little less strong because the breeding bird surveys used to generate population trends tend to peter out as you go further away from human population centres. However, many boreal songbirds are very long-distance migrants (i.e. they go all the way from the temperate boreal to South America), which is a big risk factor, and the trends that we do have don’t look very promising for most, including the Connecticut Warbler. Overall, the Connecticut Warbler is declining by about 1% per year. Most of the Connecticut Warbler breeding range is in Canada, which means that Canadians in particular have a responsibility to protect this bird.

This map shows the Breeding Bird Survey trends over the last 40 years, with areas in red declining the most and areas in blue increasing. Overall the Connecticut Warbler gets a ‘medium’ confidence in terms of how real these trends are – this is because there aren’t as many survey routes in their range as we would like, and their density is generally pretty low.

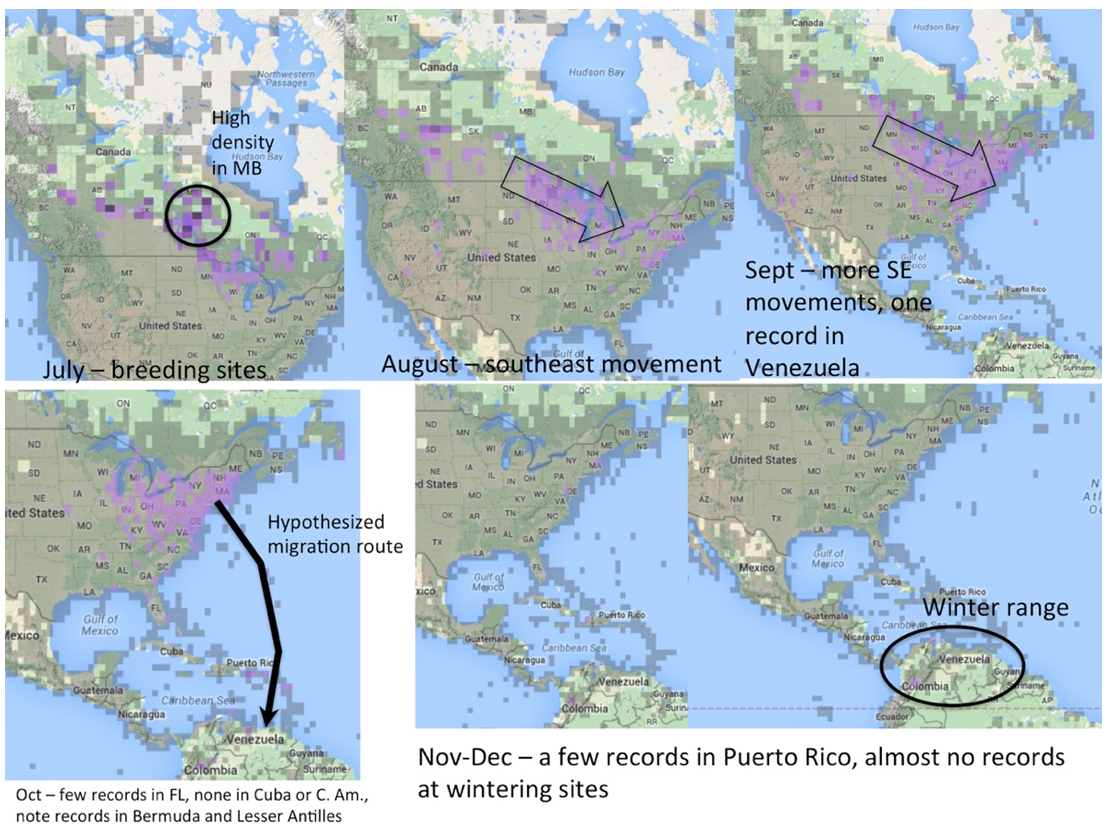

One of the potential threats listed for this species is habitat loss in the winter range. But critically, we have nearly zero information on migration, winter range, winter habitat, or winter ecology. There are only 5 ebird records for this species in the winter range. One in Bolivia, the rest in Colombia. Records in the literature are equally sparse. It’s hard to believe that a North American breeding bird could be so under-studied. Dr. Jay Pitocchelli and colleagues recently (2012) updated the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Birds of North America Species Account for Connecticut Warbler, and it is clear there are still huge gaps in our knowledge of this species. For one, it took 70 years after the original specimen was collected for a nest to be described. What we know about breeding biology is largely from a very detailed study of ONE nest in Michigan in the 1960s. Reading through the BNA Account had me more and more intrigued. Then I read this: “Some evidence for nonstop trans-oceanic migration (Monroe 1968, Wetmore et al. 1984) […] Records for West Indies are scarce, but large numbers were reported on Bermuda during Hurricane Emily on 26 Sep 1987 when 75 were grounded; previous daily high had been 3 (Amos 1991).”

Could Connecticut Warblers be trans-oceanic fall migrants, like Blackpoll Warblers?

Examining the ebird records for the fall migration period were also suggestive of a trans-oceanic flight. Connecticut Warblers are rarely detected along the gulf coast or in Florida, and there is only one ebird record for all of Central America (Panama). In contrast, they have been spotted throughout the Lesser Antilles and into northern South America. Could they be flying over the ocean from the east coast of the US directly to the Lesser Antilles or even direct to South America?

Examining ebird.org records for Connecticut Warblers shows the potential for a trans-Atlantic flight in fall.

Given the total lack of information on fall migration routes and winter sites, and the potentially mind-blowing fall migration this species might undertake, and the fact that they are a designated stewardship species of the northern forest, they are a prime candidate for migration tracking!

After convincing my supervisor Dr. Oliver Love and mentor Dr. Christian Artuso of Bird Studies Canada that this was worth investigating, last summer I captured over 30 males, and put out tiny 0.5 g data-logging backpacks on 29 of them. These tags are passively recording light levels and hopefully the birds return (with their backpacks intact!) this spring to their breeding sites near Winnipeg, Manitoba, where I will be waiting for them! I suspect they have important stories to tell.

Stay tuned for Part 2: Connecticut Warbler Fieldwork (or, how everything I thought I knew about them was wrong). View full blog here: https://birdbiologist.wordpress.com/