This is Part II of our oil spill update. Part I discussed the extent of the oil spill and the problems containing the leak, Part II discusses the impacts on local as well as migratory birds, and Part III will discuss the longer-term implications of our addiction to oil and the need to plan our future sources of energy carefully.

An oil-soaked Brown Pelican on Louisiana's East Grand Terre Island

Credit: AP/Charlie Riedel

UPDATE: Since the first update it doesn’t seem like significant progress has been made on containing the spill. While a number of newer efforts have succeeded in capturing some of the oil spewing daily into the Gulf, none have been able to fully stop the flow of oil into the ocean. BP has been able to secure around 20,000 barrels per day over the last week or so, but this is still well short of the estimated 35,000-65,000 barrels leaking daily (if not more).

When news of the oil spill first came, many experts were rightly fearful this spill would have a detrimental impact on a variety of birds. The Gulf Coast region, and especially the Mississippi River Delta, is vitally important for hundreds of bird species. The marshes, tidal flats, and wetlands provide ideal nesting and migratory stopover habitat for millions of waterfowl, seabirds, shorebirds, and other waterbirds. These habitats are also the nursery for the fish, turtles, mollusks, and other marine life of the Gulf of Mexico which make up the food supplies for these birds. Right now the nesting birds are bearing the heaviest burden from the oil spill. This includes plovers, terns, gulls, herons, egrets, rails, gallinules, and pelicans (including the Brown Pelican, which was recently removed from the endangered species list but is still highly vulnerable). Louisiana’s coast is estimated to support 77% of the U.S. breeding population of Sandwich Tern, 52% of Forster’s Tern, and 44% of Black Skimmer. Clearly a major mortality event or drastic drop in breeding success on the Louisiana Coast in species like this could have long-term implications for the health of their total populations.

The Louisiana coast is a vital region for resident and migratory birds

Credit: Gulf Restoration Network

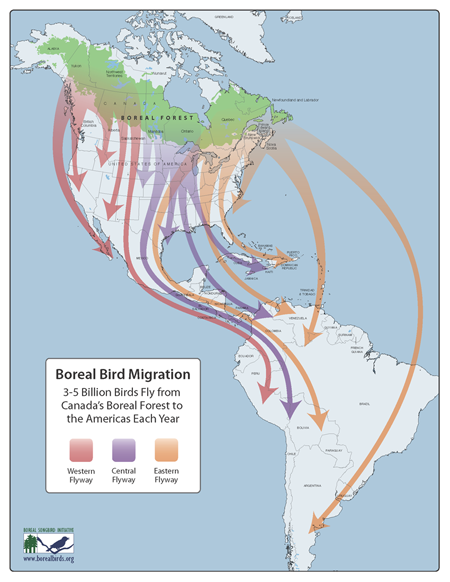

The birds that winter or use the region to feed and rest on their way south and north will begin to feel the impacts as the summer progresses into fall when these species will be migrating south. Many species of shorebirds in particular that breed in the Boreal and the Arctic start migrating back south in July. Perhaps the earliest of these migrants is the Short-billed Dowitcher, which is a species that nests almost entirely within the Boreal. By the fourth of July, I usually begin seeing flocks of this species heading south along the Maine coast on their way south.

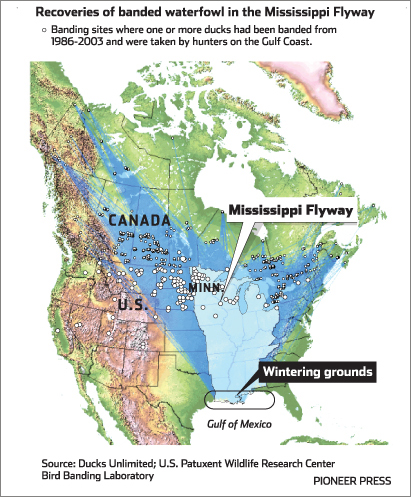

By October large numbers of ducks will have arrived back in Louisiana marshes expecting to spend the winter in areas rich with food. This includes species like the Green-winged Teal, American Wigeon, Ring-necked Duck, and Lesser and Greater Scaup which have more than 50% of their breeding populations within the Boreal. Most of these are particularly reliant on the Louisiana Coast. For example, an estimated 40% of the Green-winged Teal wintering in the U.S. are found on the Louisiana Coast. Thirty percent of scaup and 20% of both American Wigeon and Ring-necked Duck are estimated to winter there.

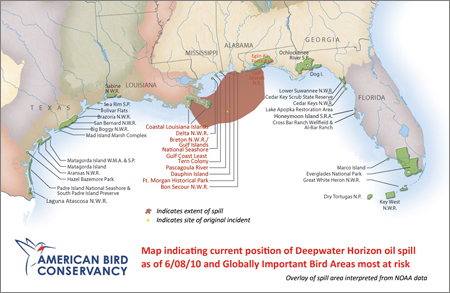

The American Bird Conservancy has a great map of some of the region’s Globally Important Bird Areas, as well as the oil slick range as of June 8 (the slick range changes daily with the currents and wind):

Audubon also has a Google map feature that is updated daily showing the oil spill area and the Important Bird Areas affected with lots of background information and video of the sites and what is going on there.

Sadly many of North America’s most at-risk species occur in the region. Some of the most at-risk that I profiled in my book Birder’s Conservation Handbook include Mottled Duck, Yellow Rail, Black Rail, Snowy Plover, Piping Plover, and Short-billed Dowitcher.

A couple of these profiles are available online:

Mottled Duck >

Black Rail >

Short-billed Dowitcher >

The Short-billed Dowitcher is one of several at-risk species in the region

Credit: Jeff Nadler

Within 10 days of the spill the first oiled birds were starting to be discovered. By May 6 oil had already reached the Chandeleur Islands, a designated Important Bird Area and important breeding ground for Sandwich and Royal Terns as well as the Brown Pelican. The slick has continued since into a number of other vital bird habitats along the Gulf Coast.

What’s more alarming (though not surprising) is that we know from past spills that the number of reported oiled bird sightings is just be a fraction of the total toll. At least 1,000 birds have been documented as killed as a result of the spill according to a Fish and Wildlife Report, but we can expect this figure to be much, much higher.

While the images of birds saturated in oil provide the most visually shocking evidence of the damage, this is only one of several problems the spill poses for both local and migratory species.

The American Bird Conservancy did a good job of compiling a list of the main risks the oil spill poses on birds, of which the following is modified from:

- The first is the immediate threat to individual birds from oil physically covering them and impeding their ability to fly, dive, see, and thermoregulate as well as becoming sickened by ingesting oil especially as they struggle to preen it off their feather. Some oiled birds are now being collected and sent to rehabilitators in the region, while others are still mobile enough to elude capture or are in nesting colonies where disturbance from trying to capture them would destroy too many nests of unaffected birds. Many birds will be killed but never collected, particularly 'plunge-diving' birds that feed in open water sometimes miles from shore including pelicans, gannets and terns.

- The second is from reduced food availability due to contamination of the marine environment that supports the fish and invertebrates upon which the birds feed themselves and their young. Many of these are the same seafood stocks that are the foundation of much of the regional coastal economy.

- The third concern is from oil impacts to bird habitat of beaches, salt marshes, and estuaries and to the eggs and young of the large numbers of ground-nesting terns and shorebirds that this region supports. The long-term effects on birds will be decreased breeding success as nests fail due to contamination of eggs that come into contact with oil and due to birds being forced from contaminated areas to marginal breeding sites or sites that are already at maximum capacity. There are often long-term impacts on habitat and ecological productivity as well that can go on for years, as has been shown from the Exxon Valdez spill.

Nest on an island off the Louisiana coast

Credit: AP/Gerald Herbert

As we can see the direct contact with oil is only a fraction of the longer-term effects this spill could have on birds. Contaminated breeding grounds and lower breeding success rates, in addition to lower food stocks, could impact species’ populations for generations.

These factors are what pose the largest threat to the birds that either migrate through or spend their winters in the region. While the majority of attention to date has been given to local resident species, there is a lurking ‘time bomb’ for many of the waterfowl and shore birds who breed further north (many of which from Canada’s Boreal Forest and the Prairie Pothole Region) but migrate to the region to spend their winters there. This includes Mallard, Northern Pintail, Green-winged Teal, American Wigeon, Ring-necked Duck, and Greater and Lesser Scaup. Ducks Unlimited estimates that 13 million North American ducks winter in the Gulf Coast and its inland marshes.

To show this, Ducks Unlimited put together a map of recovered bands on waterfowl and where they were originally banded:

Many migratory wetland-dependent smaller birds and shorebirds including Black-bellied Plover, Semipalmated Plover, Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs, Solitary Sandpiper, Least Sandpiper, Dunlin, Stilt Sandpiper, Short-billed Dowitcher, Wilson’s Snipe and many others will stop in the region to rest and feed before continuing down on their journeys to the Caribbean and South America. Since these vital habitats and food sources will still be contaminated as these birds return south, it is likely that they will be negatively impacted.

Here’s a map we put together last year of all the major flyways that migratory Boreal-breeding birds use to get to their winter homes. You can see that many species use the Gulf region to either winter in or migrate through on-route to their homes further south:

Overall, we can say that this spill happened in one of the worst places possible from a bird-centric view. Many birds have already died directly from coming in contact with oil, but as we can tell this is only a small fraction of the larger story. The damage being done to breeding, wintering, and stopover habitat as well as the unknown long-term effects on food sources mean there could be dramatic reductions for a variety of birds for years, if not decades.

There are, however, several ways you can help. The National Audubon Society has put together a help center page with multiple options depending on your location and/or budget. I highly recommend you check it out and either donate or even sign up to volunteer if you live near the affected areas!

http://www.audubonaction.org/site/PageServer?pagename=aa_HowtoHelp